The history of women in Pakistan politics is a powerful story of resilience, courage, and persistence.

From the days of independence to today’s Aurat March, women in Pakistan have continuously fought against systemic barriers, discriminatory laws, and patriarchal politics. Their struggle has not only transformed gender debates in Pakistan but also reshaped global narratives about women in Muslim-majority societies.

Historical Roots: Women and the Pakistan Movement

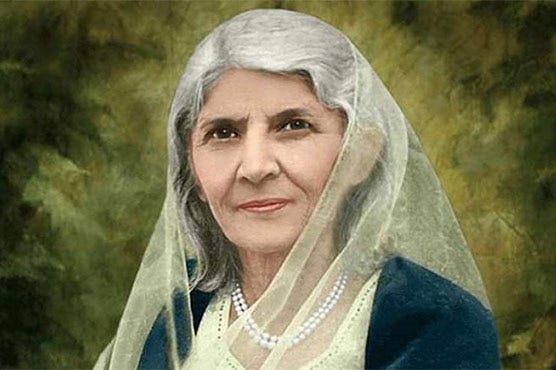

Women’s political involvement dates back to 1947, when they actively mobilized during the struggle for independence. Fatima Jinnah, known as the “Mother of the Nation,” was a vocal political figure, later contesting elections against Ayub Khan in 1965. Though she lost amid allegations of rigging, her candidacy broke cultural barriers and remains a symbol of women’s leadership

Early Foundations

In 1949, Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan founded the All Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA), which became one of the earliest civil society platforms for women. APWA worked on legal literacy, education, and community mobilization, bridging the gap between politics and grassroots issues This era laid the groundwork for later generations of activists by proving that women could organize, legislate, and contest power in the public sphere.

In 1961, the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance introduced reforms around marriage and divorce, offering women some legal safeguards

But during Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship (1977–1988), women’s rights suffered severe setbacks. The Hudood Ordinances (1979) criminalized zina (adultery) and made it harder for rape victims to access justice.

The Era of Resistance: 1977–1988

The military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq (1977–1988) marked a regression in women’s rights. His Islamization agenda sought to reshape law and society along conservative lines. The Hudood Ordinances (1979) blurred the distinction between rape and adultery, requiring four adult male witnesses to prove rape. As a result, women reporting assault were often charged with zina themselves, leading to imprisonment, social stigma, and even honor killings. By the mid-1980s, hundreds of women languished in prisons under these discriminatory laws

In this hostile environment, the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) was born in 1981. Comprised of lawyers, journalists, academics, and students, WAF became the nerve center of feminist resistance. It organized demonstrations, provided legal defense for imprisoned women, and produced counter-narratives to state propaganda. WAF’s activism was fearless, women marched in Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad, facing police batons, arrests, and vilification in the press

This era was critical because it showed that even in times of authoritarian repression, women refused to be silenced. It was here that the culture of feminist street politics was cemented in Pakistan.

Benazir Bhutto: Breaking the Glass Ceiling (1988–2007)

The election of Benazir Bhutto in 1988 marked a global milestone. At just 35 years old, she became the first woman Prime Minister of a Muslim-majority nation. For women across the Muslim world, her victory was more than a political event, it was a symbol of possibility.

Bhutto’s tenure introduced some reforms aimed at women’s welfare, including efforts to strengthen the First Women Bank and initiatives for women’s education and healthcare. However, her governments faced instability, corruption charges, and dismissals, which limited her ability to pass transformative gender legislation. Scholars argue her leadership was more symbolic than systemic, as patriarchal political structures constrained her reforms.

Her assassination in December 2007 while campaigning in Rawalpindi was a tragic reminder of the dangers faced by women in politics. Yet, her legacy endures: Bhutto remains a global icon of women’s leadership in Muslim societies, often cited alongside figures like Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher.

The assassination of Benazir Bhutto was a turning point. Her death shook Pakistan and the world, but it also mobilized women to step into political spaces with renewed urgency. The 2008 elections restored democracy, bringing the PPP(Pakistan People Party) back to power. Women gained seats through quotas, but most were still tied to male-dominated dynasties, limiting their independence.

2008–2013: Legal Reforms and Challenges

This democratic period saw progress in women-focused legislation:

- Anti-Harassment at Workplace Act (2010): First law to define and penalize workplace harassment.

- Domestic Violence Bills (2012 onward): Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan passed laws, though implementation remained weak due to resistance from conservative lobbies.

Yet, women leaders continued to face patriarchal backlash and limited opportunities for grassroots representation.

2013–2018: Representation without Power

Women’s parliamentary presence stayed steady due to quotas, but their voice in decision-making remained weak. Reserved seats were often filled by elite women chosen by party heads rather than grassroots leaders. Still, the period saw debates on honor killings, child marriage, and harassment laws gain national attention.

2018–2020: Street Power and Cultural Shifts

Women began reclaiming the streets in unprecedented ways:

- Aurat March (2018–present): Annual rallies demanded autonomy, safety, and equality, despite severe backlash.

- #MeToo Movement (2018): Sparked by Meesha Shafi’s case, it broke taboos around harassment and forced debate on justice, defamation, and women’s credibility.

These movements shifted feminism from elite circles into mainstream politics.

2020–2024: Political Decline:

In parliament, women’s progress faltered.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) Parline, showing Pakistan National Assembly women’s representation:2% in 2018.

- IPU Parline also shows approx 17.0% for women in 2024.

highlighting the weakness of reforms when parties fail to institutionalise them.

2025 and Beyond: The Unfinished Journey

History was rewritten with the rise of Maryam Nawaz Sharif. was elected the first female Chief Minister of Punjab on the 26 February 2024. Maryam, a senior leader of the Pakistan Muslim League-N and daughter of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif. She won a historic provincial victory that marked the first time a woman headed Pakistan’s largest and most politically influential province. Her election is a significant milestone for women’s executive leadership in Pakistan and illustrates both the political opportunities and the reality of dynastic politics in the country.

FromBenazir’s assassination in 2007 to the Aurat March of 2025 and Maryam Nawaz’s premiership, the story of Pakistani women in leadership and politics is one of unbroken courage. Their journey shows that while progress can be rolled back, the determination of women ensures their fight for justice and equality continues, stronger than ever.